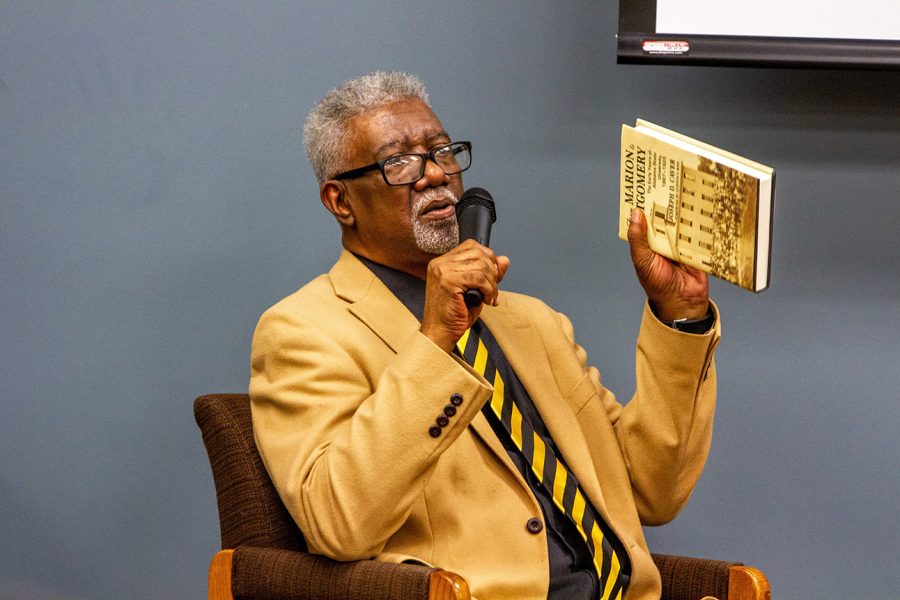

Caver elucidates the early history of the university

Photo by JAELYN STANSBURY/CHIEF PHOTOGRAPHER

Noted historian and adjunct instructor Joseph D. Caver talks about the early years of Alabama State University and the challenges that it faced in order to educate newly freed Black slaves.

February 4, 2023

Noted historian, archivist, author, alumnus and adjunct professor Joseph Caver kicked off Black History Month by lecturing about the early history of Alabama State University in the Levi Watkins Learning Center (LWLC) Lecture Hall, Feb. 2 at 11 a.m.

Caver, a former senior archivist at the Air Force Historical Research Agency at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama, and co-author of The Tuskegee Airmen, An Illustrated History: 1939–1949, is the author of “From Marion to Montgomery: The Early Years of Alabama State University, 1867-1925.

Caver referenced the Marion Nine (founders of Alabama State University) and informed the audience of how Blacks in Mobile, Alabama, met right after the abolition of slavery and decided that the only way the race could move forward was to obtain an education.

“The Marion Nine is really a result of that meeting as they came together, even though some of them were illiterate, and decided to incorporate a school for newly freed slaves in July 1867,” he said. “The ladies during that time were very instrumental in raising funds to obtain the land and the building which was later called the Lincoln School of Marion.”

Caver talked about the first principal of the school Thomas Corwin Steward who arrived in Marion, Alabama, in 1867. Steward, a former Union soldier that worked for the American Missionary Association from 1868 to 1876, was eventually elected to represent the area in the Alabama state legislature during Reconstruction. He spent his time teaching the newly freedmen how to read and write.

After five years, Steward was reassigned to Nashville to the campus of Fisk College. There he built Jubilee Hall before being sent to Washington D.C. to work on projects there. He died on Dec. 19, 1902, after suffering injuries in a railroad accident. He and his wife had five children.

Caver talked about the first president of the Lincoln Normal School, George N. Card, and how the Black citizens of Marion were never fond of his appointment as president but seemed to be appeased when William Burns Paterson of Tullibody Academy was appointed president of the Lincoln Normal School and University for the Education of Colored Teachers and Students at Marion, Alabama, in 1878.

According to Caver, during Paterson’s administration at Marion, the campus was expanded by five acres to provide better facilities. In 1880, the first class of six (three men and three women) graduated from the Normal Department with all six being employed thereafter in the schools of Alabama (two in Pike Road in Montgomery County).

He talked about Paterson’s love for flowers and how his love grew into one of the floral industries of the South, Rosemont Gardens. He cleared up the myth that the university was relocated to Montgomery because of a fight that occurred between the students of Howard College and Lincoln Normal.

“It was really Baptist politics that caused the university to move to Montgomery,” he said. “The Baptist citizens of Marion were trying to keep Howard College in Marion, but they eventually moved to Birmingham (Samford University) … and the Lincoln Normal University was moved to Montgomery.”

One of the students who was in attendance, Tre’von Conner, asked Caver “If the university was founded in July 1867, why do we celebrate Founders’ Day in February?”

Caver said that William Burns Paterson’s birthday, which evolved into the Founders’ Day celebration, was initiated by one of the elementary school faculty, Mary Francis Terrell, who thought Paterson was sent by God. That annual birthday celebration evolved into the Founders’ Day celebration.

Howard Robinson, Ph.D., the associate director for archives and cultural heritage at the university, explained that Caver’s story of the early beginnings of the university is a perfect way to begin the celebration of America’s Black History Month because a myriad of things has taken place on its campus or by its alumni that are told in Caver’s book, which has positively changed the course of Black history in America and the nation.

“Caver in his book has captured the very essence of how ASU has so greatly contributed to the celebration of this important holiday,” Robinson said, “and reminds us how intertwined it is in America’s celebration of this important holiday.”