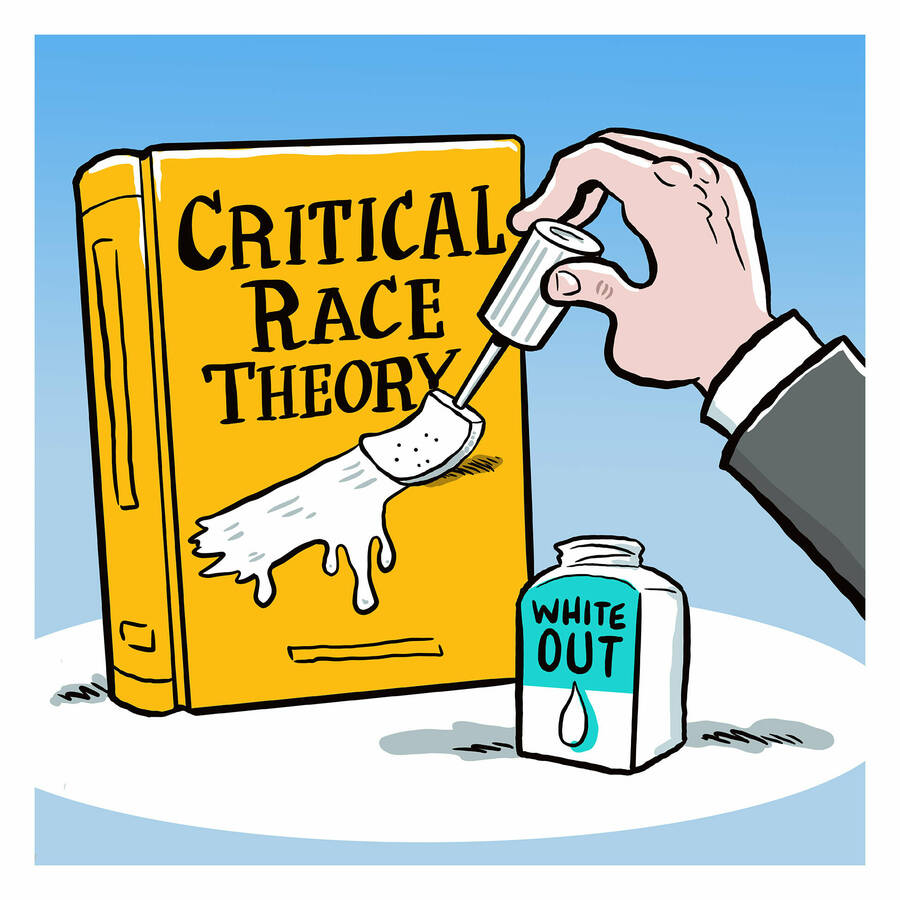

Column: Why has ‘Critical Race Theory’ activated so much discourse

June 20, 2021

The academic concept of “critical race theory” has become a hot topic over the last few weeks that is generating fights over school curricula at the state, local and federal levels. People are arguing over whether elements of critical race theory should be included in diversity training, military training as well as both the public and private sector workforce training.

After Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida signed legislation requiring the state’s public colleges and universities to survey students, professors, and staff members about their political views on Tuesday, in an effort to crack down on intellectual “indoctrination” on college campuses, the matter has moved much closer to home. DeSantis said that college campuses are “hotbeds for stale ideology” and were “not worth tax dollars, and that’s not something that we’re going to be supporting going forward.” In fact, the bill states that annual surveys would assess the “intellectual freedom and viewpoint diversity” and determine “the extent to which competing ideas and perspectives are presented” and whether students, professors, and staffers “feel free to express their beliefs and viewpoints on campus and in the classroom.”

Because the possibility of a similar law could be passed in the Alabama legislature for students, faculty, and staff at public colleges and universities, The Hornet Tribune staff felt it necessary to examine this concept and bring clarity to what it actually means.

What is it and how did it get started?

The core idea behind critical race theory is that racism is a social construct (an idea that has been created and accepted by the people in a society) and that it is not merely the product of individual bias or prejudice, but also something embedded in legal systems and policies. It argues that the legacy of white supremacy remains embedded in modern-day society through laws and institutions that were fundamental in shaping American society. Generally speaking, it rejects the idea that laws are inherently neutral, even if they are sometimes applied unevenly. Its backers say that American society, framed by the Constitution, gives a leg up to white people—but that it could be made more equitable if more white people acknowledge societal advantages of having been born white.

The basic precepts of critical race theory emerged out of a framework for legal analysis in the late 1970s and early 1980s created by prominent legal scholars Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw, and Richard Delgado, Mari Matsuda, and Patricia Williams. These scholars share an interest in recognizing racism as a quotidian component of American life (manifested in textual sources like literature, film, law, etc). In doing so, they attempt to confront the beliefs and practices that enable racism to persist while also challenging these practices in order to seek liberation from systemic racism.

Bell, who was Harvard Law School’s first tenured Black professor and is considered by a number of historians as one of the founders of critical race theory, started his work to examine “American political history through the role that the law played in developing, maintaining and pushing” racial discrepancies in U.S. society—challenging the notion that the law has been a means by which each citizen is treated the same.

However, some legal scholars who have disagreed with the theory argue that it is difficult to prove that critical race theory is institutionalized in the law, particularly where laws do not mention race.

According to the Wall Street Journal, Dan Subotnik, a professor of law at Touro Law Center in New York, argues critical race theory fails to take into account how laws have changed over time.

“It was good to put it on the table, and it raises lots of good questions,” he said. But, he added, “that doesn’t mean there shouldn’t be a counterview that says that enormous changes have taken place in this society and continue to take place in this society, and a lot of people in both races support the changes that have been made,” such as the introduction anti-discrimination rules in housing and employment.