Harold Franklin, Auburn University’s first Black student, dies at age 88

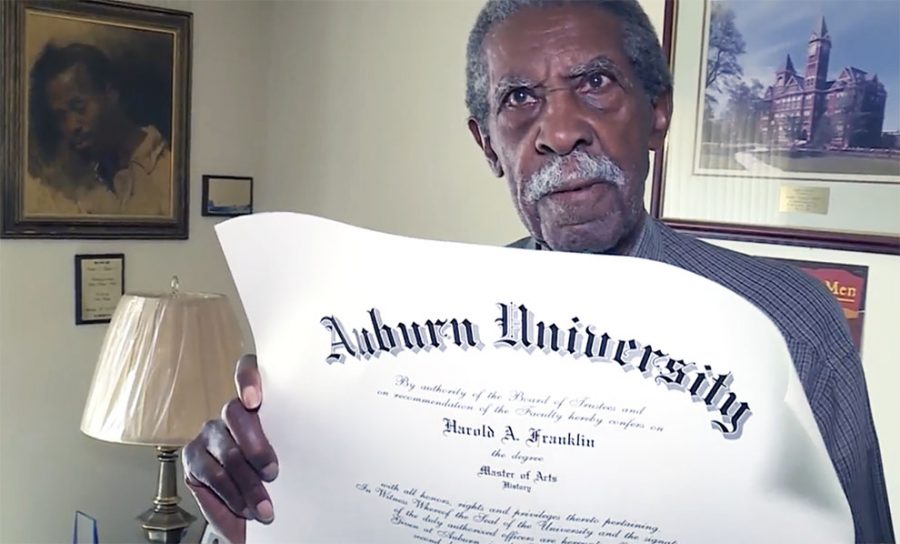

Harold A. Franklin displays his master of arts diploma that he received from Auburn University after waiting for 54 years.

September 11, 2021

A 1962 summa cum laude graduate of Alabama State University died this week, but not before he made history as a history major.

Harold Alonza Franklin, Auburn University’s first Black student, who had to sue the university to gain admission, died Thursday at his home in Sylacauga, Alabama. He was 88.

Finally, after gaining admission, Franklin was escorted onto the campus by armed guards. He had to walk 200 yards without police protection to register. Franklin integrated Auburn as the university’s first Black student on Jan. 4, 1964, enrolling as a graduate student.

In classes, white students refused to sit next to him. When he completed his coursework, Franklin wrote his thesis and submitted it again and again.

According to The Washington Post, Franklin gave a comprehensive account of the events during his tenure at Auburn.

“They were angry with me because I sued them,” Franklin said. “They tried to make it as difficult as possible for me to get my degree from there.”

Unfortunately, it worked as he could not obtain a degree from Auburn University as planned in 1965.

“Each time I would carry my thesis to be proofread, they’d find an excuse,” Franklin said. “Sometimes, I didn’t dot an ‘i.’ One of the professors told me: ‘Yours has to be perfect because you are Black, and people will be reading yours.’ ”

“I told him I had been to the thesis room and read the theses by white kids,” Franklin said. “Theirs were not perfect. I couldn’t understand why they couldn’t accept mine.”

Franklin completed draft after draft. Each was rejected. Finally, he realized he was hitting a stonewall of racism as he was pursuing a master’s degree that he never received after his thesis was repeatedly rejected, as late as 1969.

“I said, ‘Hell, what you’re telling me is I won’t get a degree from Auburn?’ Then Franklin, a tall man who had grown up in the segregated South, told the thesis committee, “To hell with it.”

And he left.

Years later, he would earn a master’s in international studies from the University of Denver and go on to a successful 27-year career as an educator in higher education after leaving Auburn in 1965. He was able to teach history at Alabama State University, North Carolina A&T State University, Tuskegee Institute, and Talladega College before retiring in 1992.

Franklin initially was not allowed to defend his thesis at Auburn.

Because of research completed by Keith S. Hébert, Ph.D., an associate professor of history at Auburn, who was reading a news story about Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey (R) wearing blackface during a skit at Auburn more than 50 years ago, Hebert uncovered Franklin’s story because a reporter had reached out to Franklin for a comment.

“All these years, Auburn had constructed the narrative that Franklin had just left the university of his own volition,” Hebert said. “During all those commemorations and discussions about integration at Auburn, they overlooked the story about this man who was cheated out of the degree he rightfully earned.”

Auburn’s story of racism had been whitewashed in the same way other universities and cities had cleaned up their racist history.

Hébert, who is also the director of Auburn’s public history program, decided the history department needed to “make right” what happened so many years ago. Hébert began researching and found the department had rejected Franklin’s initial proposal to write about the civil rights movement.

“I wanted to write on the civil rights struggle,” Franklin said. “One of the professors told me it was too controversial.” Instead, he wrote a thesis about Alabama State College, the historically Black institution he graduated from.

“Here was a guy on the front lines of Black activism, and the department said, ‘You can’t write that.’ They shoehorned him into writing the history of Alabama State College. He played nice and said he would do that. But after a while, they seemed outright hostile to him finishing it,” said Hébert, who is white and grew up in Louisiana witnessing racism there. “They held him to a different standard because he was Black. It had to be perfect. It was designed to force him to leave.”

In 2019, Hébert contacted the graduate school dean to get the required approval to offer Franklin a chance to defend his thesis. But Hébert did not know whether Franklin would agree. And he did not know whether Franklin still had his original thesis.

Once he arrived at Franklin’s home, he learned that Franklin was still in possession of the original thesis.

Hébert became Franklin’s adviser, and they worked to get the thesis uploaded onto a computer.

“Here’s a guy I’ve talked about in class a lot,” Hébert said. “I’ve taught about his lawsuit in the history of Alabama class every semester. Here, I am hanging out eating lunch with this guy.”

“Normally, in a thesis defense, it is the committee and you,” Hébert recalled, “but on this day, the entire faculty attended. The dean of the graduate school attended. A lot of people wished him well.”

Hébert asked Franklin one question. And Franklin launched into an hourlong lecture.

“I asked Harold how did you end up writing the history of Alabama State University for your thesis? It was an open-ended question. I knew it would cover his life story. He quickly went to, ‘I never wanted to come to Auburn anyway. I didn’t want to write this thesis. And then you didn’t accept it.’”

For the next hour, Franklin retold his life story, explaining how he ended up at Auburn walking across a hostile campus in January 1964.

In the library, the committee listened to Franklin’s story so many years later.

“He had a strong performance,” Hébert recalled. “There wasn’t a dry eye in the house. He told a powerful story.”

Hébert read a statement of apology.

“I had read that statement a million times because I didn’t want to break down,” Hébert said. “It was an acknowledgment of past wrongs. I’m part of a society that committed those wrongs. A lot of white people, even my students, say, ‘I didn’t do anything.’ But they fail to understand the privilege white people benefit from and the negative impact on others.”

Years later, “Auburn celebrated Franklin as the first Black student but never told the full story,” Hébert said.

“I’m just about speechless after all these years,” Franklin — who graduated with honors from Alabama State College in 1962—said after walking across the stage at Jordan-Hare Stadium in December.

“I realized it wasn’t going to be easy when I came here as the first African American to attend Auburn, but I didn’t think it would take this long. It feels pretty good. I’m glad I could do something to help other people, and my mom and dad always taught us that, when you do something in life, try to do something that will help others as well.”

He was supposed to be awarded his degree at Auburn’s graduation, but the pandemic disrupted the ceremony.

Instead, in June, Franklin received his degree in the mail. By then, the country was consumed by Black Lives Matter demonstrations following the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor.

For Franklin, the clashes felt so familiar.

“I’m glad to see the protests happening now,” he said. “Black people’s lives should matter to everyone else. We are human, like everybody else, and deserve respect, like everybody else.”

In 2021, a plaza area was created to accompany the marker adjacent to the library, and it was unveiled by Auburn University officials during a special ceremony this past November.

“Dr. Franklin was a trailblazer,” Auburn University Trustee Elizabeth Huntley said. “I would not be here today if it was not for his courage to enroll at Auburn and, in the process, desegregate the university. Dr. Franklin broke the barrier so that generations of African American students, including my husband, daughter, and me, could graduate from Auburn University.

“It takes a tremendous amount of courage to do the right thing and create opportunity for others. I will always appreciate Dr. Franklin’s tenacity, perseverance, and his Auburn spirit that was never afraid.”

Born Harold Alonza Franklin on Nov. 2, 1932, in Talladega, Alabama, he was one of 10 children of George Franklin Sr. and Henrietta Eugenia Williams Franklin.

He married the late Lilla Mae Sherman, and they had one son, Harold Franklin Jr. She preceded him in death, and after retiring from teaching.

“Harold Franklin was a civil rights icon who overcame enormous obstacles to help change the world and push Auburn University toward becoming a better version of ourselves,” Hébert said.

.