Alabama’s first Black state trooper made history

February 10, 2023

The Alabama State Troopers were once known for their brutality and callous disregard of the Constitutional rights afforded the citizens of the United States, especially the rights of African-Americans. The civil rights movement of the 1960s was marked by numerous cases of violent and sometimes deadly interventions by Alabama troopers such as James Bonard Fowler who shot and killed a young voting rights activist named Jimmie Lee Jackson, sparking the Selma to Montgomery marches of 1965.

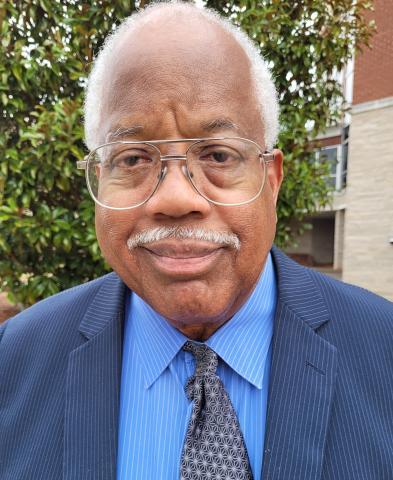

In March of 1972, just seven years after the troopers’ violent attacks against marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge gained national attention, the nation again took notice when Montgomery native Tyrone Anderson – an African-American and Alabama State University alumnus (class of 1969) – and two other men of color were hired by the Alabama Department of Public Safety as State Troopers, working in the midst of a police force that numbered more than 950 White men.

“Needless to say, when myself and Elbert Dawson of Tuskegee and Leon Hampton of Birmingham entered the Trooper Academy that was then near Montgomery’s Garrett Coliseum as the first-ever Black State Troopers, we turned quite a few heads and shook up what had traditionally been the vehicle that enforced in Alabama racial segregation, Jim Crowe laws and the Ku Klux Klan’s ideal of a White dominated statewide status-quo,” said Anderson, a soft-spoken, yet no-nonsense, 75 year-old.

“Very few of the nearly 1,000 rank-and-file White troopers ever said a harsh word to me – but I must say that very few of them ever had anything at all to say to me or Dawson or Hampton (both of whom are now deceased); however, most all of the officers in charge of us were fair and cordial in a distant sort of way, which might have been influenced in part because we were only present and hired because of a Federal Court order forcing the integration of what had once been the personal domain of segregationist Governor George Corley Wallace, who in 1972, was still advising his state attorneys to fight the hiring of Black troopers as prescribed by the Federal District Court.”

The agency was under an order from Federal District Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. to hire one black for each white until the state police force was one‐quarter black.

In a story published by The New York Times on March 30, 1972 – the date of Anderson’s hiring – Col. Walter L. Allen, head of the troopers, downplayed the order of Montgomery-based Judge Johnson by saying the reason Blacks were hired was that “the state had a ‘critical’ shortage of State Troopers.”

Judge Johnson’s order was “the very first to specify precise hiring ratios to achieve a racial balance in a state agency,” stated the New York Times article.

Johnson’s desegregation order for the law enforcement agency was appealed by Governor Wallace, who lost his action after a review by the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals.

TROOPERS WERE ONCE INSTRUMENTS OF OPPRESSION

When reviewing the history of the State Troopers prior to 1972, one sees a multitude of brutal acts of violence and oppression, followed by arrests, jailings and sometimes funerals of people whose only crime was peacefully demanding the right to vote, or to be allowed access inside a public building, to be served food in a public restaurant, to take their children to a city park to play, or to date or marry a person of a different race.

ASU’s acclaimed Civil Rights Movement expert, Dr. Howard Robinson, characterized Alabama State Troopers as the very embodiment of evil in what some refer to as “the bad old days.”

“When many think of the Alabama State Troopers, one of the most common images many visualize is what they did on March 7, 1965, at Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge, when they brutally assaulted over 600 peaceful civil rights supporters, led by John Lewis, who were both protesting the murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson and demanding the right to vote,” said Robinson, from the Civil Rights Room housed in the ASU Library (Levi Watkins Learning Center). “The Troopers, led by Major John Cloud, came after the 600 with clubs, tear gas and bull whips and many were severely injured, including Lewis, who suffered from a cracked skull.”

Even The Montgomery Advertiser, then considered a racially biased publication, expressed shock at the sheer chaos and carnage that took place at the hands of the troopers at the bridge and in an article, referred to the incident as a “Police Riot.”

“It wasn’t called ‘Bloody Sunday’ for nothing and that is why the hiring of Mr. Anderson and his two associates, three Black men, was such a novel and refreshingly big deal nationwide. It evoked a feeling of hope that just perhaps Dr. King’s vision of the ‘Beloved Community’ might just be taking hold,” Robinson said.

A BACKGROUND IN FINES ARTS

When hired, Anderson, who graduated from Alabama State with a degree in Fine Arts, had been teaching high school in Covington County, Ala. At first, he speculated he would hold the law enforcement job for “maybe two years”; however, the two years morphed into a 30-year career with the State Troopers, which eventually saw him promoted to the rank of Captain and his becoming the state’s top criminal investigator and the commander of the Alabama Bureau of Investigation (A.B.I.).Anderson’s stellar career also included holding the record for the largest amount of drugs seized at one time in Alabama – a feat that occurred at the Montgomery Airport in the 1980s.

WE STAND ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS

Another notable Black law enforcement officer, ASU employee Col. (Ret.) John E. Richardson, said the bravery of Anderson and his two cohorts inspired him to join the State Troopers in 1985. Richardson’s career eventually led him to become the second Black Director of the Alabama Department of Public Safety and director of the State Troopers.

“It was a very brave thing for Capt. Anderson to put himself out as a State Trooper during an age when it could still be dangerous for a Black man to wear a Trooper uniform,” stated Richardson, an Opelika native.

Richardson said Anderson taught him in a class on investigations at the Trooper Academy.

“The action of Tyrone and his two fellow Black Troopers in 1972 set the foundation for men and women of color to become state law enforcement officers. I salute Capt. Anderson’s effort and action. All three men deserve to be remembered during Black History Month because they made Black history.”