Why the Black press is more relevant than ever

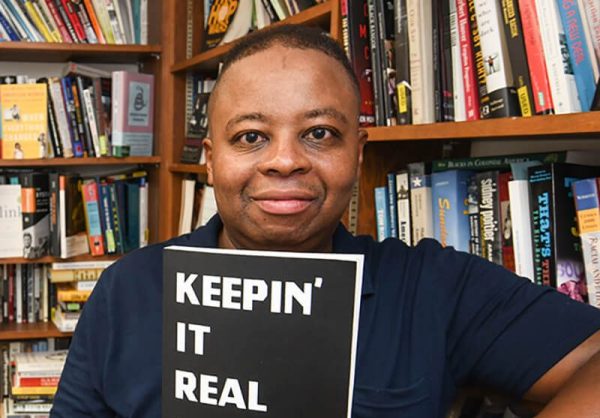

David A. Love, J.D. serves as the executive editor of BlackCommentator.com. He is a journalist, commentator, human rights advocate, a professor at the Rutgers University School of Communication and Information based in Philadelphia.

February 11, 2023

For years, newsrooms across America have had a problem with a lack of diversity and inclusion. People of color are underrepresented among news organizations, which do not reflect the makeup of the general population and have made little progress in the past decade.

Although non-whites make up about 40% of the US population, journalists of color comprise only 16.55% of newsrooms’ staff in 2017, according to the American Society of Newspaper Editors (ASNE) Newsroom Employment Diversity Survey.

Larger newsrooms and digital news organizations are a little better – 23.4% and 24.3%, respectively – but not much. People of color are only 13.4% of newsroom leaders.

This comes at a time when society needs and demands more inclusive news. It’s been 190 years since the creation of the Black press, and it’s as relevant as ever.

In the absence of an inclusive environment, the quality of journalism suffers. Certain stories are simply not reported, or are told without the nuance or perspective the circumstances require. The Black press has filled that void for generations. And with the advent of digital platforms, a baton has been passed to Black millennial writers to continue presenting narratives, with underrepresented points of views, that would otherwise go missing – and do not necessarily reflect the white men who dominate the industry.

Far beyond using social media for entertainment, shopping or communication, African-American millennials have elevated Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and other platforms to raise public consciousness about the issues impacting Black people. The hashtags #BlackLivesMatter and #OscarsSoWhite are prime examples of this phenomenon.

According to Nielsen, 55% of Black consumers between 18 and 34 spend at least an hour on social media each day, 6% higher than all millennials. In addition, 29% of black millennials spend three or more hours daily on social media sites, 9% higher than that of all millennials.

While Black millennials fall below their counterparts in the percentage of leisure time spent on social media, they exceed the general millennial population in their overall presence on Twitter, Tumblr, Google+ and Whatsapp. That online presence has translated into the creation of a network of Black news outlets specifically creating content that will meet readers and viewers where they are.

Additionally, when the mainstream media covers a particular issue, the Black press may cover it with a completely different angle – if not a different issue altogether. For example, the Black press rejected the mainstream media narrative that white “working class” support for Trump was primarily economic in nature, reporting instead on the presidential candidate’s appeal to white solidarity, raw racism and the scapegoating of minority groups.

After all, white economic angst by itself does not reconcile the fact that whites always have fared better than their African- and Latino-Americans. And while the mainstream news organizations have framed the NFL protests through the prism of patriotism and support for the military, the Black press has focused on the crisis of police brutality and racial violence that underlie the athletes’ decision to take a knee during the national anthem.

Fifty years ago, when unrest rocked cities across the nation as a result of police brutality and systemic racism, the Kerner Commission – an 11-member commission appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson that highlighted racism for its role in a surge in urban riots – took the news media to task.

“We have found a significant imbalance between what actually happened in our cities and what the newspaper, radio and television coverage of the riots told us happened,” the Kerner report said.

“Our second and fundamental criticism is that the news media have failed to analyze and report adequately on racial problems in the United States and, as a related matter, to meet the Negro’s legitimate expectations in journalism. By and large, news organizations have failed to communicate to both their black and white audiences a sense of the problems America faces and the sources of potential solutions.”

The Commission made a number of recommendations, including that news organizations employ Black people beyond mere tokenism and in positions of real responsibility, and that they publish newspapers and produce programs that acknowledge Black people, who they are and what they do.

Although newsrooms have made some progress, it’s not where it should or needs to be. But by empowering themselves and their followers – without gatekeepers and intermediaries in the traditional media sense – young, Black journalists have reached a broad audience. They can educate and mobilize others to act on a given issue, and connect with local, national and global social justice movements.

A videographer or documentarian can broadcast a crime in progress – such as a police beating of an unarmed motorist – live and in real time, before an audience of thousands if not millions. In that regard, technology is the great equalizer, a check on the abuse of official power and a call to reform harmful patterns and discriminatory practices.

From its inception, the Black press has been a change agent by shining a light on the plight of Blacks and giving them the power to write and report on their own narratives. In New York in 1827, Rev. Samuel Cornish and John B. Russwurm began publication of Freedom’s Journal, the first Black-owned newspaper in America. Excluded from white venues and often insulted in their absence, Black voices found the need to tell their own stories.

“We wish to plead our own cause. Too long have others spoken for us. Too long has the public been deceived by representations, in things which concern us dearly,” wrote the editors in their first edition.

Throughout the Civil War, Black newspapers were centers for political debate on the war and emancipation, and advocacy for black soldiers. During Jim Crow and the reign of Klan terror, the Black press fought against segregation, demanded equal rights for African Americans and helped elect politicians to office.

The Chicago Defender, which had demanded federal intervention from President Woodrow Wilson to stop lynchings, played a role in the Great Migration by urging a mass exodus of Black people from the South.

In the 1890s, journalist Ida B. Wells led a campaign against lynching at considerable personal risk. Born a slave, she wrote about the injustices of racial segregation in the South. A mob descended upon her Memphis news office, destroyed her equipment and threatened her with death.

Over the years, many Black publications disappeared. Others learned to navigate the new landscape, and a plethora of new Black media emerged with a strictly online presence, impacting the manner that black people digest and make sense of the news.

The days of “reading the paper” are long gone for many, but what remains the same is that the Black press doesn’t look like the theoretical textbook case of objective journalism – and it was never meant to be – whatever that means to you.

When narratives are told from the perspective of a black lens, perhaps there are no two sides to a story. Perhaps there is only one side, or numerous sides with various textures and shades. What is certain is there is a sense of responsibility to the community, advocating for that community and telling their stories from their perspective.

A digital environment arms African American millennial writers with tools that enable them to carve out their own territory in their unique and innovative way – exercising free speech and contributing to a healthy democracy, and staying true to the proud history of the Black press.