2,000 more lynching victims brought to light in EJI’s new Reconstruction era report

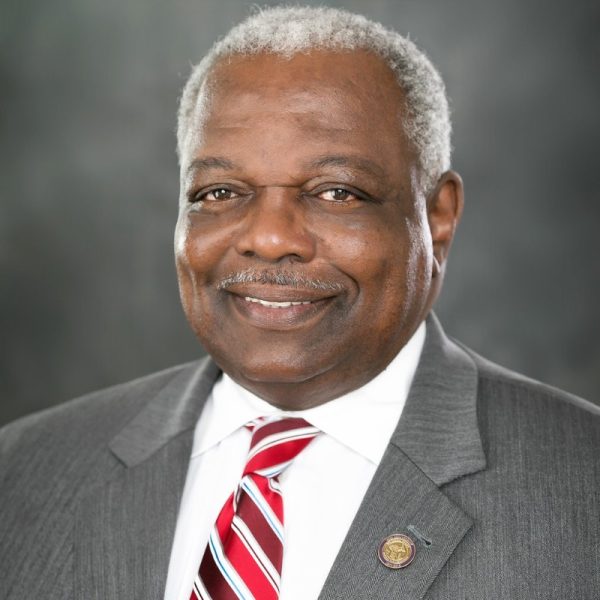

(Photo: Mickey Welsh / Advertiser)

Bryan Stevenson, Executive Director of the Equal Justice Initiative, is shown standing before jars containing soil from the sites of confirmed lynchings in the state of Alabama as he discusses the opening of the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice at the EJI offices in Montgomery, Ala. on Friday April 13, 2018.

June 16, 2020

After the 15th amendment gave freedmen in Eufaula the right to vote, the city’s new Black electorate used their majority to elect a white pro-Reconstruction candidate as city court judge in 1870. When they attempted to re-elect him four years later, the city’s white residents waged a terror campaign.

As hundreds of Black citizens gathered in town to vote, they were met by police who arrested some on sight and jailed them under accusations of fraud. A group of white men forced one Black man into an alley and threatened to arrest him if he refused to vote against his own interests.

While Black onlookers protested, a shot was fired into the air. Shortly after, a large mob of white men returned with guns, spreading out over the street and perching in windows where they blanketed the crowd of Black voters with bullets.

Six Black people were killed, and more than 80 injured. About 500 voters fled the scene before casting a ballot.

When a Black man named Hilliard Miles identified some of the white mob’s attackers, he was charged and convicted of perjury. One of the perpetrators he identified was Braxton Bragg Comer, a man who would later become the 33rd governor of Alabama.

The Eufaula massacre and many others revealed in a new report released today by the Equal Justice Initiative, detail for the first time how racial terror lynchings and assaults on newly freed men, women and children following the Civil War during the period of Reconstruction between 1865 and 1876 were used to intimidate, coerce and control Black communities with the impunity of local, state and federal officials — a legacy that has once again boiled over, as nationwide protests sparked by multiple police killings and extrajudicial violence against Black Americans call for an end to centuries of hostility and persecution.

“We cannot understand our present moment without recognizing the lasting damage caused by allowing white supremacy and racial hierarchy to prevail during Reconstruction,” EJI’s Director Bryan Stevenson said in a statement.

While Reconstruction’s emergence was a time of great hope and promise for African Americans, it was a daily reminder to their former white captors of loss and destruction.

“If there was any period of time where white animus toward blacks was omnipresent, particularly in the South, it was certainly during the time of Reconstruction,” said Alabama State University History and Political Science Chair Derryn Moten.

Black women and men sought education and economic advancement. Black men ran for political office and were elected as sheriffs, mayors and legislators. And white Southerners who saw people they had deemed as “property” emboldened with the rights of full citizenship, fumed.

“That was the dawning of African Americans’ new freedom. You had the ratification of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendment. You had the first Civil Rights Law enacted,” Moten said.

“This was also the time period when the Klan and other terror groups came into fruition. There was a lot of pent up anger and hatred toward African Americans, and lynchings were one manifestation of that.”

In the 12-year period EJI analyzed using digitized Freedmen’s Bureau records, congressional testimonies and newspaper reports, they found more than 2,000 Black victims killed during the Reconstruction era alone — a staggering figure they admit is likely far higher but severely limited by lack of available documentation. In comparison, EJI documented more than 4,400 victims of racial terror lynchings over the course of seven decades between 1877 and 1950.

While lynchings and racial attacks against freed men and women were documented in greater frequency in the South, the report’s findings span as far North as Newburgh, New York and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Despite Constitutional amendments passed by Congress to enfranchise and empower Black Americans, state authorities often disregarded these laws and the Supreme Court itself struck down protections for Black citizens in favor of “state’s rights.” When Congress ultimately abandoned Reconstruction’s mission, further economic exploitation, violence and exclusion ensued. “Our continued silence about the history of racial injustice has fueled many of the current problems surrounding police violence, mass incarceration, racial inequality, and the disparate impact of COVID-19,” Stevenson said.

In 1904, the United Daughters of the Confederacy decided to impress their version of history in downtown Eufaula. Among the streets where the town’s black voters were shot down by white vigilantes, a “towering Confederate monument” now stands. S.H. Dent, a former soldier, who watched and possibly participated in the massacre, spoke at its unveiling.

![In a speech from the White House, he explained that the Department of Education would “forgive $10,000 in outstanding federal student loans” and that Pell Grant recipients would “have their debt reduced [by] $20,000.” Only those making less than $125,000 a year would qualify for this relief.](https://asuhornettribune.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/J-Biden-475x255.jpg)