Original Selma marcher dies on eve of tribute; others pledge to fight on

In 1965, Annie Lee Cooper participated in the march for Black voting rights in Selma — and decked a cop for trying to keep her from the ballot box.

March 4, 2023

Billy clubs hitting bodies, screams for help, tears dripping from the gas in the air. Hundreds of protesters were there on March 7, 1965, demanding the right to vote, and as decades pass, they don’t forget the violence they saw that day in Selma.

“I don’t have to tell you about the people we’re honoring,” organizer and fellow foot soldier JoAnne Bland said on Saturday morning. “These people are still doing great things in the community, and we lost a great one yesterday morning.”

Selma foot soldier Alice West, 93, died on March 3, just two days before the 58th bridge crossing and one day before the annual Foot Soldiers Breakfast. Both events honor her and the hundreds of other civil rights activists who marched in Selma for the Black right to vote.

Other original Selma foot soldiers — the men and women who marched for voting rights in 1965 — looked up from the crowd that sat inside Selma High School. Each of them remember that Sunday vividly.

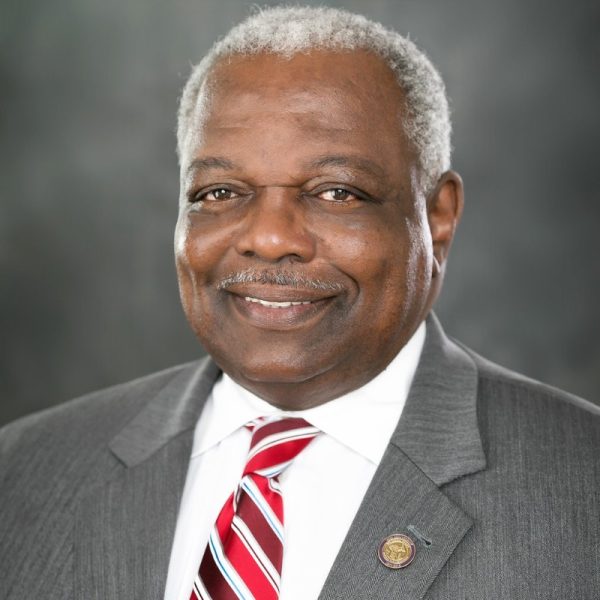

The foot soldiers who were honored Saturday include Richard Smiley, Albert Southall, Charles Mauldin, and the late Annie Lee Cooper.

Richard Smiley’s fight

16-year-old Smiley returned to his foster home on March 7, 1965, to find the door locked. He had just escaped the violence of state troopers who turned him and other voting rights activists back once they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and he had nowhere to go.

Before leaving for the march that would turn into Bloody Sunday, Smiley’s foster mother told him that if he joined the march, he would no longer have a place in her home.

“I told her I understand her job, and I had a moral obligation to march and fight for the rights of Black folks,” Smiley said in a statement.

“600 young people got beat back down on that bridge. There’s blood stains on that bridge,” Smiley said while accepting his honor. “Enjoy the celebration, but understand, we’ve got to fight on.”

Alabama has a long history of Black voter suppression, and Smiley wants Selma residents to exercise the rights they have today. He wants people to mobilize their neighbors and remind each other why he and 599 other men and women marched across the bridge 58 years ago.

Albert Southall’s impact

Southall has lived in Selma for most of his life. He graduated from R.B. Hudson High School in 1965, the same year he joined the civil rights movement.

On Bloody Sunday, he marched toward the front of the crowd. Then, 14 days later, he marched again, walking all the way to Montgomery while carrying the American flag.

Now, he owns and operates Southall’s African American Literary and Arts Museum and Gallery, keeping Black history and Black art at the forefront of Selma’s mind.

“It’s people like Albert who keep history alive,” Bland said as she presented him with a plaque and a foot soldier jacket. “If generations to come do not remember where we’ve been as a nation, they cannot take us where we want to go.”

When accepting the honor, Southall expressed his thanks, specifically to Dallas County district judge Vernetta Perkins, who spoke at the breakfast about the importance of developing young leaders.

“I heard you,” Southall said.

Annie Lee Cooper’s persistence

Cooper posthumously received the same plaque as Smiley and Southall. She died on Nov. 24, 2010, following her 100th birthday.

“There’s no one here for us to present the award for Miss Cooper to, but we know she was courageous,” Bland said.

She lived just down the street from Cooper at one point, and she remembers Cooper’s tenacity. For years, Cooper spoke to every group of tourists she came across, telling the story of her quest to register to vote in Alabama.

When she lived in Pennsylvania, she was able to vote, but when she moved to Selma to take care of her mother, she found that wasn’t so easy. Cooper took and failed the Jim Crow-era literacy test many times, but though she failed, she didn’t give up her goal.

When Cooper returned to the courthouse in January of 1965 to take the test again, Dallas County Sheriff James Gardner Clark Jr. poked at her neck with a billy club and kicked at another man in line. She fought back and was immediately arrested.

“Three days later, swollen face and body, Miss Cooper was back at that courthouse trying to register to vote,” Bland said.

Charles Mauldin’s support

Like Bland, Mauldin is both a foot soldier and an organizer of the breakfast. Starting in 2006, without many people knowing, he organized and funded the entire event. When Bland found out what he was doing, she stepped in to help. Now, they work together.

Mauldin was just three rows back from the front of the march on Bloody Sunday. He was close enough to John Lewis that he says he can still remember the sound of a state trooper’s club striking Lewis.

He didn’t identify himself as an activist initially, just an “observer of little incidents.” That changed over time.

When he started working with the civil rights movement, Mauldin said he saw clearly that the solution was in non-violence.

On Saturday, Bland, other foot soldiers and a crowd of people honored Mauldin for his continued activism and commitment to preserving history.