From a student servant to a public servant

Minka uses critical thinking skills and political experience to bring a new society closer

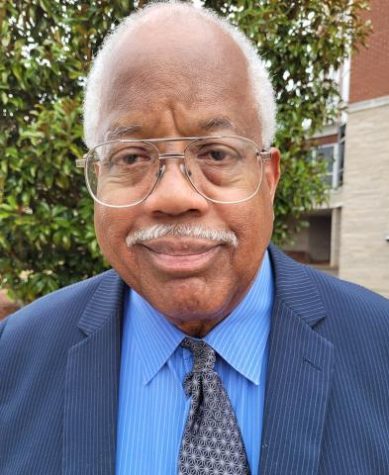

Adofo Minka, a St. Louis Public Defender, prepares for an upcoming legal case. Minka attended St. Louis School of Law and is a 2009 alumnus of Alabama State University. Minka began his law career in Jackson, Miss. as a public defender and later returned to St. Louis to serve in the St. Louis Office of Public Defenders.

March 1, 2021

Black youth are often encouraged to attend college because many of their elders deem that a college education is a necessity for them to be competitive in today’s job market. The collegiate path is emphasized to high school students, nationwide, through seminars, college fairs, pamphlets, and college recruiters.

Alabama State University alumnus Adofo Minka was not one of those high school students. Being the first person in his family to attend college, he was unsure if college was the correct path for him, but his undeniable brilliance and urge for a place of critical thinking led him to the Hornet’s Nest.

Born with the name Bryan Weaver, he is originally from St. Louis, Mo. He grew up in a two-parent household along with one younger sister. Minka attended Jennings Junior High School, where he first became interested in the idea of attending college. He said, “I really didn’t know much about college … It wasn’t something that was talked about deeply among my parents until I got to college. It was just assumed that it was something that I was going to do because other people my age were talking about it.”

Though he was unsure about his decision, his interests in psychology and dreams of being a teacher motivated him to make college the next step on his journey.

“It was in my mind that this was the next step in life, in terms of higher thinking,” Minka said.

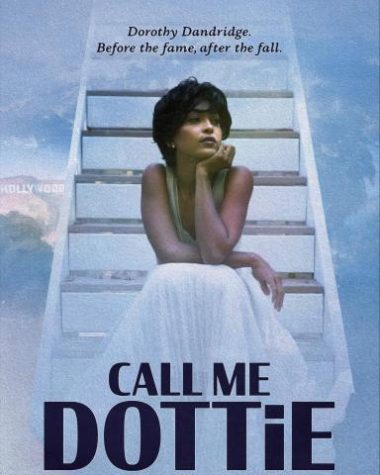

Minka graduated from Jennings Senior High School in May 2005 and began his college career at Alabama State University that fall semester. Coming from St. Louis, Minka shared that he chose to attend Alabama State University because of a familiar face that was already enrolled there. His childhood friend, Marcus Henderson (who is now a noted film star), enrolled at the university two years earlier on a football scholarship. Henderson’s stories of the university’s culture persuaded Minka to join the Hornet family.

“When he would come back,” Minka said, “he would always talk about the things going on at ASU and how much fun it was … He was down there so I knew that I would have somebody to look out for me and show me the ropes of things.”

Though the culture is what attracted him, the opportunities and academic advancements are what molded Minka into the man he is today.

During his time at ASU, Minka ran cross country and served as a writer and editor-in-chief for The Hornet Tribune, and eventually became the Student Government Association (SGA) President during his senior year.

“Those things formed my development, formed my growth, my coming-of-age, and helped me to look at things from various perspectives,” Minka said. “They are all experiences that I think I needed to see the world in a critical way and to think the way I do today.” During his time with both organizations, Minka worked to bring African American injustices and hierarchical corruption to the attention of the student body. His current and profound ideas as well as his voice comes from his time “writing, thinking, and articulating ideas on a weekly basis” with The Hornet Tribune.

As SGA president, Minka organized the visits and presentations of notable African American activists, professors, and free-thinkers.

“We had the L. D. Reddick Lecture Series where we brought in various scholars from around the country,” Minka said. Though there were many influential speakers, he especially remembers Professor Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Ph.D., from Ohio State University and author of ”Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama’s Black Belt” (2009), Molefi Kete Asante, Ph.D., from Temple University where he leads the African American Studies program, Claud Anderson, Ed.D., the author of book ”Black Labor White Wealth” (1941), and Harriet A. Washington, author of book ”Medical Apartheid” (2006).

Along with the seminars, Minka and the student government officials would hold dinners with these visiting scholars to hear their teachings in a more intimate setting.

“We were trying to engage students in a formal kind of classroom setting and in an informal way over dinner,” Minka said.

Also as a student, Minka was able to create relationships with professors that influenced his growth as a free thinker. He credits Derryn Moten, Ph.D., Kenneth Dean, J.D., Lee Dowdy, Ph.D., and Corie Muhammad, M.Ed., for encouraging him to delve into controversial topics such as race, social conflicts, and administrative corruption. Muhammad is also responsible for Minka’s participation in a discussion group, called the Dedicated Intellectuals of Our People (DIOP).

“We would have various discussions about race and a lot about the oppression that black people were facing from the majority … At the time, it was very integral for my development,” Minka said. From these talks of racial conflicts, Minka gained a personal interest in the social hierarchy and political domination.

Minka also credits his interest in law to Moten, as he set him up with an internship with the Equal Justice Initiative and Bryan Stevenson in 2007. This experience shifted his goals from pursuing a doctorate in history to becoming an official of the law.

“I really wanted to fight on behalf of the people who didn’t have the means to get a good attorney,” Minka said. “I wanted to keep the state from crushing people. I’ve always liked the idea of being involved with a fight for a good cause.” This goal led to his enrollment at St. Louis University Law School, where he exhibited his natural instinct to lead, as he served as the president of the Black Law Student Association for two years.

In 2012, Minka graduated from Saint Louis University Law School and married Detroit native Shanina Carmichael, who is also an alumna. After graduation, Minka and his wife moved to Jackson, Miss., to work with the Malcolm X Grass Roots Movement and social activist Chokwe Lumumba, a criminal defense attorney, and a black nationalist.

“I decided that I was going to work with him at his law firm to be mentored and learn to practice law,” Minka said. It was during this time that Weaver legally changed his name to Adofo Minka, meaning “a brave person who loves justice.” This name was suggested by scholar Asante.

Minka shadowed Lumumba and worked on his campaign team in 2013, helping him to get elected into office as mayor of Jackson, Miss. The next year Minka passed the Mississippi Bar Exam. Unfortunately, Lumumba passed away a few months after gaining the position. Considering he relocated to Jackson solely to work with Lumumba, Minka was at a loss upon his mentor’s death.

However, his experience with law and city officials landed him a job with the Hinds County Public Defender’s Office in 2015, where he worked until he returned to St. Louis in September 2020 where he is currently employed with the Missouri State Public Defender’s Office.

After working as a Public Defender for five years, Minka has come across all types of cases. Through it all, he states that his most memorable case happens to be a murder case where he first served as the lead counsel. Though he lost the case at the time, it is currently in the process of getting appealed. He recounts the case as a moment that helped him to develop his career.

“It was a learning experience,” Minka said. “When you have someone’s life on the line, that isn’t something to take lightly.”

He acknowledges that his work is one that takes great strength and sacrifice, but those are prices he is willing to pay for the good of the community.

“When you work on those cases, you spend hours preparing,” Minka said. “You are tired from staying up all night through the different days of the trial, but it is always rewarding to see your client be vindicated and able to go back to their family.”

Outside of practicing law, Minka also lives life as a journalist taking on topics of racial, social, and economic unrest in the United States.

Stemming from his work when he worked on The Hornet Tribune, he continues to delve into controversial conversations.

“Politics is my true passion and this is just a way that I advance it, through writing,” Minka said.

He has articles published on multiple platforms such as the Black Agenda Report, National Workers Union Journal, New Politics, and more frequently on the Jackson Free Press. Some of Minka’s titles are as follows: “Jackson’s Policing Betrays Poor and Working-Class Black People,” “Stop Talking About Corruption: The Nature of Ethics and Patronage in Politics,” and “No ‘Free Kills’ Unless We Are Black in Jackson.” Minka’s articles are full of critical analysis of all levels of politics along with how they affect vulnerable communities. He aims to expose the injustices at all levels.

“Many black people in the black political class use their identity as social capital to integrate into a system that basically justifies the use and abuse of poor people,” Minka said. “They get ordinary black people to justify their rulership above society in the name of black unity, and really encourage black people to live vicariously through them, even though they continue to catch the same kind of hell they caught before these people got these positions.”

Based on his writings, he wants the community to learn that common people have the potential to govern. He said, “The only way that oppressed people will upend this is if they arrive on their own authority and take back their power.”

Minka takes pride in knowing that his work comes from the purity of his heart. He believes that compassion and empathy are the principles that make him so passionate about his work.

“I think you have got to have those things when you are doing this work,” Minka said. “You have got to be able to care about people and care about what you are doing. You have to have some kind of pride.”

His compassion is what fuels his dream of establishing and endorsing a form of politics that serves all, no matter what race, education level, or personal beliefs.

When asked what he wanted to be remembered for, he said, “… as someone who stood on principles. Someone who opposed injustice and wrong-headed political thinking, regardless of the color of one’s skin … It is my hope that I make some small contribution to the establishment of something new, a new society, a new beginning.”

Today, Minka lives in St. Louis with his wife and two sons, Amari and Asa. When he is not urging for political and social reform, he enjoys exercising and spending time with his children.

“I take care of my mind and body,” Minka said.

According to Minka, those peaceful practices are needed after a hard day’s work of fighting systemic corruption.

To current students, he urges them to pay attention to the world around them.

“Pay attention, think, and investigate the ideas that people are presenting to you as a college student,” Minka said. “You should look at everything with a critical eye.” It is from that critical awareness that personal experience and opinions develop, and those views are what establishes you as an individual. Being an individual who can push back against the norms and conventions of normative society and a free thinker maximizes your impact on your community.”