Hall found his passion in the field of education

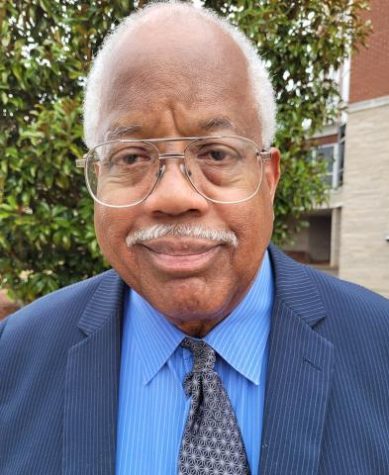

PHOTO BY DAVID OLANIRAN/MANAGING EDITOR FOR VISUAL AND MULTIMEDIA

George Washington Carver Senior HIgh School principal Gary Hall takes a minute from his busy schedule to talk about his career as a salesman, teacher and principal. As he enters his 18th year as an education administrator, his key to success is sharing his own struggles as a high school student, utilizing his skills in communication and sales, and adopting the Hornet hospitality.

August 28, 2021

It takes a number of interacting variables for a flower to grow. Though it starts as a seed, it takes the right soil, adequate sunlight, proper water levels, and other environmental conditions to reach its final form. Without those surroundings, that same seed would only be a speck, full of untapped potential.

Some would argue that the same concept applies for humans. It takes a special combination of conditions for humans to grow, an idea strongly believed by ASU alumnus Gary Hall, a principal of 18 years at George Washington Carver Senior High School.

“I blossomed when I got to Bama State,” he said with a glow.

Hailing from Mobile, Alabama, Hall grew up as the youngest child of Betty and Lorenzo Hall. With his father being the first Black man to own a Texaco service station in the area, and older siblings who excelled academically, Hall was faced with high expectations. Also, considering that many members of his extended family resided in Mobile, Alabama, Hall was able to reap the benefits of having a close-knit and well respected family.

“My dad used to tell us when we would go somewhere, ‘Always remember you represent the Hall name,’” said Hall.

Holding childhood dreams of becoming a lawyer, he was known for his knack for discussion and discourse.

“A debate was always great for me,” he said. “I would always antagonize people or get them in situations where we could talk about issues. I would end up wearing them down!”

He carried those skills with him to W.P. Davidson High School, where he admits to not being the best student himself. Though he was part of the football team and a member of Distributive Education Clubs of America (DECA), he adopted a more rebellious nature than a scholarly one.

“My brother probably graduated cum laude. Well, I graduated, ‘good laude,’” Hall said.

Upon his high school graduation in 1984, he took the nontraditional route by joining the workforce instead of attending a university. He became a wine salesman at Premier Beverages in Birmingham, Alabama as a way to establish himself in the working world. In this position he enhanced his skills in communication, became familiar with professional settings, and took the time to mature. The opportunity also allowed Hall to gain an appreciation for education, as he realized that a college degree would be his ticket to success. It was this appreciation that encouraged him to enroll at Alabama State University in 1991.

“The catalyst behind that was going into the workforce, and the workforce pretty much told me, ‘Hey, you are going to be nothing without that degree,’” he said. “That pushed me to attend college.”

Still having aspirations of becoming an attorney, Hall enrolled as an English major. These plans quickly changed after taking advice from Johnnye M. Witcher, Ed.D., an English professor who kickstarted his long running career in education. Seeing Hall’s potential as an instructor, she sold him on the benefits of majoring in language arts, teaching and encouraging him to spend time in Zelia Stephens Early Childhood Center.

“I went over [to Zelia Stephens] and said, ‘Okay, I could probably do this,’” he said. Ironically finding solace in the field that troubled him as a child, Hall found his new path. “Education picked me, I would not say that I picked it.”

In his next years as a Hornet, now a language arts major, Hall was forced to manage life as a full-time student and part-time professional. He worked as a shoe salesman at the department store that was known as Parisians, now known as Belk, in order to pay for his tuition. Though it was sometimes difficult, he insists that his maturity allowed him to stay focused, as he had already sown his wild oats.

“I was all about the business,” Hall said. “Some of the other things that other students were doing, I had already done it all.”

It was also his work at Parisians that allowed him to create lasting relationships with many faculty members, as the female faculty and staff members came to him for all their shoe needs. Servicing administrators such as Alma Freeman, Ed.D., Mary Mithcell, M.S.,Vivian DeShields, Ph.D., Witcher and more. Not only did they nourish him with all of his academic needs, but funded many of his shoe sales, resulting in hearty commissions.

“Those ladies kept me in the right direction,” Hall said. “Really, they put me through college!”

Though he spent the majority of his days studying and working, he made sure to find moments to enjoy Hornet life. His favorite memory as a student was his first time attending a basketball game at Charles Johnson (CJ) Dunn Arena now known as the Fred Shuttlesworth Cafeteria. Dressed for the well-anticipated after party, Hall attended the basketball game wearing a silk shirt in a more than crowded facility.

“It was so hot in there I almost fainted,” Hall said. “I sweated out my silk shirt! It was ridiculous!”

Though his shirt may have been dampened, his spirit was lifted as he experienced the vivacious energy and school pride that could only be found in that arena. Believing there is none other like it, he values those moments of intimacy and togetherness with his fellow Hornets.

Along with the memories, Hall was able to achieve an accelerated course of study due to his strong support system within his faculty. He highly regards his time studying under a number of professors, but especially Michael Romanoski, Ed.D., a well-respected member of the education department.

“That Romanoski,” he said. “He would whip you up in the classroom and then invite you over to his house to play basketball.”

He expresses that only at ASU would he have been able to form those personal, genuine, and sincere relationships between instructor and student.

Hall graduated from ASU in 1995 with a bachelor’s degree in language arts. He walked across the stage on a Sunday, and landed his first job on the following Monday. He was employed as an English teacher at Carver High School in Montgomery, Alabama, a predominantly Black school with a huge legacy, but at that time the school was going through some changes. This would, unknowingly at the time, mark the start of his legacy of rejuvenation and reform at Carver.

From his own life experiences, Hall was able to relate to his students in ways that many educators could not. By sharing his own struggles as a high school student, utilizing his skills in communication and sales, and adopting the Hornet hospitality, he was able to build a special bond.

“I think by opening up to them, telling them I did not go straight from high school to college and that I took a U-turn, they understood I had it just as hard as they did,” Hall said.

Within the four years in this position, he made sure to impact as many students as possible, in any way possible. He helped to organize school supply and clothing drives in the community, vouched for weekend food bundles to be taken home by students who would otherwise go hungry, and more. Even in situations where students did not want to be helped, Hall was there. He humorously remembers presenting a lecture on the outside basketball courts, where one of his students decided to skip class. Though perceived as a nuisance at the time, that became a lesson the said student would never forget.

“I think that is why I come here everyday,” he said. “I think I can make a difference.”

He eventually decided to pursue an administrative role, utilizing his master’s degree in education leadership received from ASU in 1997. Hall accepted the position as principal of McIntyre Middle School in Montgomery, Alabama, a secondary school that fed into Carver High. He adopted leadership of the school during troubling times, and while it fell short in many aspects, it boomed with potential and spirit.

“I went in there, we forged a relationship with the teachers and counselors and we got the students to do what they needed to do,” Hall said.

By knowing the best way to impact the students is through catering to the teachers’ needs, he first set out to maximize their work experience. He remembers jotting a list of teacher complaints and suggestions on a dry erase board for the faculty to add to, and made it his mission to remedy every one of their problems before any of his own.

“I had a great support system, and I treated them right,” he said. “It was a process. You have got to know what is broken before you try to fix stuff. I was going to see what worked and then apply it to what I needed to be done.”

From these efforts, Hall was able to bring McIntyre Middle School out of the School Improvement Plan, a state-mandated set of goals working towards higher rates of student promotion, improved test schools, and overall achievement.

After four years at McIntyre, he returned to Carver High, but this time as principal. Beginning his tenure in 2003, Hall has been the head of the Wolverine Nation for the past 18 years.

“The Wolverines are proud people now,” he said. “If you want to pick a fight, just talk about the Wolverine Nation. They will be ready to fight, and I will be right there with them.”

Priding himself on the close-knit family amongst the school, he knows the school could not run without its community.

“Alabama State and Carver have the same kind of deal,” he said. It is all about the family environment.”

Known for producing a number of professional athletes, notable political figures, doctors, and many more, the community of Carver understands the importance of providing the right conditions for the student’s growth. The community of giving and attitude of gratitude allows Hall to establish personal relationships with alumni, faculty and students. Knowing many community members by first and last name, he knows support is the key to success.

“I know I have got support,” he said. “As long as I do right by these children, they are going to support me. They believe in no child left behind.”

With goals of increasing college and career readiness, Hall has enacted programs within the school to prepare his students for the adult world. From encouraging dual enrollment to social media etiquette, professional-grade trade courses, or even speaking on the phone with sports recruiters, he makes sure all aspects of their future are bright.

“We talk about FAFSA,” Hall said. “We talk about GPA. We talk about credits, colleges they have applied to, scholarships applied for… Just to get the kids exposure.”

His efforts prove to be effective as Carver High School remains comparable to the magnet schools of Montgomery, Alabama in regards to average standardized test scores and GPA.

“We really get it done here,” he said. “I put my money where my mouth is. My kids went to a magnet school for eight years. I wanted them to come here. You see people from every walk of life right here. If you can navigate the waters here, the world has nothing on you. You can go out and get it.”

Though he has all the support and success he could ask for, there are a few challenges that come with Hall’s title. In efforts to recover from the hit of the pandemic, he has had difficulties implementing plans set in place by Montgomery Public Schools (MPS) at Carver High.

“I do not believe that one pill fixes all problems,” he said. “I am going to benefit the children. Yes, we are team MPS, but I am team Carver first.”

From his time as a Hornet, Hall has learned the power of transparency and tough love between instructor and student. He finds it is sincerity that motivates the Wolverine students as they acclimate to this new normal.

Through it all, Hall regards watching his students flourish to be the most rewarding part of his work.

“If I had to do it all over again, I would not do it any other way,” he said. “Just seeing these kids walk across that stage, and knowing we prepared them for life the best way we could… I want them to get out and see the world.”

He hopes to leave to his students the importance of community, as it was the community that allowed for his growth as a Hornet, and the community that allowed for Carver’s growth.

“I want them to understand that you have got to reach back and help the next one up,” Hall said. “I understand we are all on a bus. It does not matter who drives. He can drive or she can drive, as long as we are all moving in the same direction.”

In his personal life, Hall is the proud husband of Gina Sanders Hall, and father of Myles, 17, and Mya Hall, 15. He pledged Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. in 1991 and has been an active member ever since. In his free time, he enjoys showing support at his childrens’ and students’ extracurricular activities, while also dabbling in a bit of golf.

“I try to golf,” he said. “The concept of getting that little ball in that little hole, and going out on all that green and walking are just, ugh. I like driving the golf cart, though! I can do that for you.”

He wishes all the best to the Hornet students of today. He remembers all of the accountability, support, and love that ASU offered him as a student and hopes it provides the same for today’s generation.

“I know what it was,” Hall said. “I do not know what it is today, but I really hope that a little bit of that ole Bama State spirit is still there.”

It is that spirit that allowed him to blossom, therefore allowing his students to blossom, ultimately a cycle of support and success for the people of both Wolverine Nation and Hornet Nation.