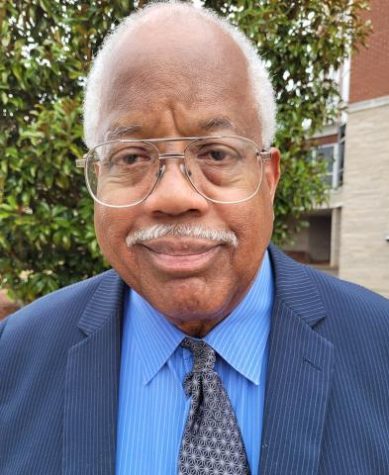

Averett promotes entrepreneurship among college students

Since its inception, Heritage Barber Shop, owned and operated by Vladimir Averett, reflects Black empowerment by design. Averett and his partner Carlos Vaughn began to hire young Black men in the community to work in the shop and do for themselves.

September 25, 2021

“Poverty is a state of mind,” Averett notes. “As far as I am concerned, I grew up wealthy because my parents instilled so many morals and values within their children. They taught me the importance of having an excellent work ethic.”

Alabama State University (ASU) Class of 1993 graduate Vladimir (“Boo- Man”) Averett was born and raised in Phenix City, Alabama, a city about 112 miles from Montgomery, Alabama. Averett had a Christian upbringing and grew up in a close-knit family with a father who was a truck driver and a mother who worked at a factory. He credits his father for dubbing him with his renowned nickname, “Boo-Man.”

“I came from a structured family,” he said. “My family consisted of my father (Melvin Averett) and mother (Reuther Averett). I have three siblings total, two older sisters (Phyllis and Calinda) and a younger brother (Melvin Bernard Averett). My eldest sister is about 15 years older than me, and my younger brother is about 5 years younger than I am.”

Averett notes that the importance of getting an education was made clear to him from a young age. While his parents did not have the opportunity to complete their formal education, they heavily promoted education in the household.

“My father only completed up to a third-grade education,” he said. “At that time, boys who were of age had to leave school to tend to a farm. My mother got her G.E.D. My parents taught me two very valuable life lessons, ‘How to love and how to work hard.’”

From these lessons about the importance of having a great work ethic, Averett decided to start working as an adolescent. His first job was as the neighborhood candy boy at 10 years old. He would pay his older sister to take him to wholesale stores, stock up on two-cent treats like popsicles and hard candy and sell them to the children in the community.

“Coming out of Phenix City with limited resources, we didn’t have a lot, but we went to church every Wednesday and Sunday like the typical Black family,” Averett said. “My parents instilled principles in us that made us mature for our age.”

During his high school years, Averett got involved in athletics and played cornerback on the school’s varsity football team. He did not want to be a collegiate athlete but was more inspired by the coaches who were pillars of the community. He credits them with instilling within him the significance of competing and teamwork. It was in high school that Averett also became involved in vocational training, learning carpentry, and barbering. In March 1987, Averett joined the United States Army Reserve and began basic training.

“I graduated from Central High School in 1987, home of the Red Devils. It was the only high school in the city, so everyone respected each other. At that time, it was a predominantly white school, about 60% of the student body was Caucasion.”

Although Averett attended a predominantly white school, there was never any animosity between the different races. The lack of racism and prejudices is largely due to the economic status of the students that attended.

“In Phenix City, there were no rich kids,” he said. “We got along well with all of the races, and it was a very diverse group of people. As long as you respect my culture, I will respect yours.”

During the Tuskegee versus Morehouse football game hosted annually in Columbus, Georgia, Averett became more familiar with some potential Black colleges that he could attend. He felt that attending a Historically Black College or University (HBCU) was his only choice because he desired to see African Americans in leadership positions.

In the beginning, Averett had plans to attend Tuskegee University, but that quickly fell through after realizing that his parents would not be able to afford it. However, his entire life Averett grew up surrounded by ASU graduates who taught him in school and were well-respected community members. He credits his uncle Willie Thomas (ASU Class of 1976), with the honor of introducing him to Alabama State University.

“Once my uncle introduced me to Alabama State, it was over with,” Averett said. “I came and visited the campus with another graduate, Mr. Wendell Price. I fell in love with it. I began thinking about all of the outstanding teachers, pastors, and community leaders that were graduates of ASU, and all these people were my role models. So from that point on, it was no question where I’d be going to school.”

Averett’s declared major was social work with a minor in psychology. He also took elective classes in the College of Business Administration. While at ASU, Averett would cut the hair of students and professors who were kind enough to give him the opportunity. In addition to this, Averett decided to follow in the footsteps of many great men from his hometown who were members of Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc.

“I became a member of Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. in 1992, and I also served as a member of the SGA,” he said. “Coming from a background of limited resources, I had to work, but I was very hands-on in the community within these organizations.”

The Black Power movement of the early 90s greatly impacted students at the time, and Averett soon began listening to and following the teachings of the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan, an American religious leader and political activist who heads the Nation of Islam. He notes that Farrakhan’s teachings of Black people “doing for self” really resonated with him. Every night, Averett and his peers would tune into the ministers’ lessons, and he became a member of the Nation of Islam in 1997.

While many ASU professors and faculty impacted Averett’s life greatly, Dr. Robert Stone, Ph.D., who taught psychology and human services, quickly became one of his favorites.

“There were no wrong answers in his class,” Averett begins. “He made me think. If you thought about something, you had to explain it.”

“I have so many favorite memories at Alabama State. I remember when we won the football SWAC championship in 1991, that was an exciting time. Coming from Phenix City, there was definitely a family atmosphere. There were about 25 of us from the same city, and we were like an organization within itself. I mean, we were close-knit. We stayed together, and we partied together. I remember taking road trips with them. One thing about Alabama State University, you’re going to find a family here.”

Averett graduated in 1993 with a 2.8 grade-point average. He jokes about not graduating as a “cum laude” student. While he acknowledges his GPA, he also distinguishes his livelihood and the lives of many other college students.

“I was a hard worker,” Averett said. “I joined the Army Reserve at 17 and stayed for 6 years. When I came to college, I wasn’t the typical 18-year-old freshman because I had experienced being away from home during basic training and my mindset was different.”

After graduating, everyone around Averett asked the age-old question, “So what are you going to do now ‘Boo- Man’?” While Averett’s true passion was in barbering, he was faced with the pressure of joining the corporate world. However, with no real plan in place, he was convinced by Allen Stewart, Ph.D., to go into a master’s program in education.

Going to graduate school was his next step.

“I graduated in May and was focused on business,” he said. “I didn’t really want to be in grad school, but I was in love with my college sweetheart, Yolanda Montgomery Averett (a 1995 graduate of ASU), and I wasn’t ready to leave her. She’s a few years younger than I am, so I decided going to grad school would make sure that I was around her and give me some time to figure out my next step. Dr. Stewart got some money together for me and paid for me to attend grad school. ”

During this time, Averett cut hair at a local shop and made $500 a week. At this point, he began speaking with his business partner and friend Carlos Vaughn about putting together some money and opening a barbershop of their own.

“I looked in the mirror and saw that what I was doing was satisfying everyone else, so I figured, ‘why not satisfy yourself?” he said.’ “I told Carlos if we get serious about this and pool some money together, we could make something happen. 1994 came around, and Carlos and I were staying in an apartment and saving money. We really worked hard and paid $1,600 to secure a duplex. That’s how serious we were. In 1995, we opened Heritage Barbershop on the corner of University Drive and Hall Street.”

Since its inception, Heritage Barber Shop has reflected Black empowerment. Not by coincidence, but by design. Averett began to hire young Black men in the community to work in the shop and do for themselves. One of the first people on board was a talented Alabama State University basketball player named Kirby Fortenberry.

“Carlos and I went to Kirby and asked him if he wanted to get on board because he was cutting the whole basketball team’s hair,” remarked Averett. “Another young brother named Isaiah Pinkston was next. We raised him, his uncle introduced us to him, and we taught him how to cut his sophomore year of high school. He was like our little brother. Carlos and I embedded everything we had into Pinkston. So when we opened up the shop in 1995, there were four young guys trying to make it the right way.”

Although Averett and his colleagues were in their early to mid-20s during this period, they were far beyond their years in wisdom, largely due to the principles that they studied in the Nation of Islam. They instilled great moral principles throughout the community through their words and actions.

“We weren’t womanizers,” Averett said. “None of us were going to have multiple girlfriends, because you can’t be successful if you aren’t focused. We had morals, and we were going to be solid men in our business. These are principles that we hold to this day. Young men that come into the shop, we tell them to pull up their pants and listen to their parents. We were in the Nation and studied the teachings. These were the guidelines that we spread among the community and the staff. I believe that the main reason why Heritage has grown so much is that we have such strong moral values.”

Throughout the years, Averett has maintained his mantra of being a “shining star amongst unconscious people.” He explains that the barbershop is not about greed and profit but is truly a reward for Black America. The foundation of the business was built upon high moral standards and maintains this into the modern-day.

“Step by step, we can grow the community,” he said. “Ladies that come into the shop, we teach them about the character of themselves. They’re our sisters, and we are very protective of our sisters. Heritage is an embodiment of our history, which isn’t just about rap music. It’s about strong people who have overcome obstacles and set a foundation.”

In his personal life, Averett enjoys spending time with his beautiful and supportive wife, Yolanda Averett. He has two daughters in college, Nia (eldest) and Mya (youngest) Averett.

“When I proposed to Yolanda, I remember her aunt came to me and said, ‘you’re going to have to do more than cut hair to take care of my niece,” Averett said. “I was 23 years old with a dream that not everyone understood. But when I see her now, she asks how I’m doing, and I tell her, ‘I’m still cutting hair’ with a big smile. I feel blessed that my wife did not feel the same and saw the dedication in me. The way that I was studying and preparing for this. I tell older people today, “A mustard seed of doubt can kill a dream.”

Being such a well-respected man of the community, Averett has many friends and clients who donate gloves, sanitizer, and other miscellaneous items to the shop. Yolanda provided the barbershop with a technologically advanced temperature checking system that Averett humorously notes “she must have spent too much on it, because she won’t tell me how much it cost.” However, he truly appreciates it as it not only protects his safety but the safety of his beloved customers and staff.

Entrepreneurs have to be prepared for unexpected obstacles as well. The COVID-19 pandemic taught Averett a lot about the importance of appreciating family time.

“The pandemic made me appreciative of the time that I got to spend with my wife and two children. It really sat me down,” he said. “My time is important to me and I realized that it’s also important to my family. Prior to the pandemic, I would let customers come into the shop past closing time. These customers survived for 8 weeks without getting a haircut. They can wait until the next day when we open again. My wife appreciates that, and I value the time that I spend with her even more.”

As a supporter of young Black entrepreneurs, Averett leaves the door open to local barbers who are interested in doing it “the right way.” He trains many young Black men in the community who want to learn how to cut hair.

“I would be short of my blessings if I refused a young man who wanted to learn how to cut hair,” says Averett. “Every barber in my shop will put a seed of knowledge within him. Even if you may not be the right fit for our shop, it’s still an honor to instill that knowledge within a man who wants to do it for himself. God blessed us with a unique talent, and it’s our duty to pass it on.”

Today, Heritage Barber Shop is located at 1334 Carter Hill Road in Montgomery, Alabama, practically walking distance from the university that impacted his life so much. The name Heritage was inspired by Averett’s roots in the Nation of Islam, and he feels the name represents the reward of doing for self and celebrates the culture. Inside the barbershop, Averett has chosen to sport that classic Bama State black and gold, in addition to many collegiate articles and ASU paraphernalia hanging on the wall. The shop is filled with the smiling faces of the customers who Averett refers to as family members and partners.

“We have family working here from age 18 to 71 years old. Once we welcome you to the family, you’re a member for life.” Averett remarks jokingly.

A hard worker and business owner by nature, Averett promotes entrepreneurship amongst collegiate students today. He notes that the drive of students who are doing the groundwork to open their own business inspires him a great deal.

“It’s great when someone chooses to do it for themselves, in spite of being taught about the traditional route our whole lives,” he said. “It’s always commendable when someone wants to create wealth for their children and the generations to come. However, it doesn’t happen overnight. I tell people all the time that straddling the fence isn’t going to work. You have to put in your 10,000 hours and be all in. The climate of business today is even better than when I was opening a business because everyone wants to work for themself. That’s a great climate to be in.”