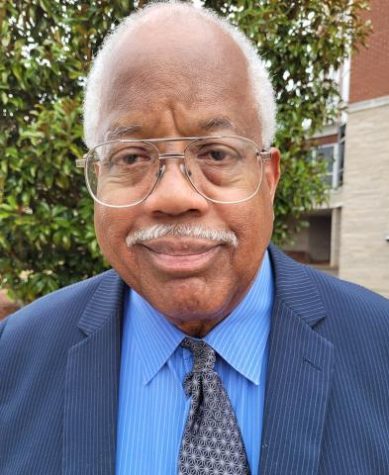

Williams advises students ‘to thine own self be true’

PHOTO BY ESAELYNN CAMERON/STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER

Longtime faculty member and Women’s Sports Coordinator Barbara Williams reflects on her tenure at Alabama State University and the contributions that she made possible for university women.

October 3, 2021

The terms “pioneer” and “trailblazer” usually refer to a person who helps create or develop new ideas or methods. Many strive to make an impact similar to what those words embody, but not all can. True trailblazers and pioneers find themselves making the most of what they are given by going above and beyond, being led by their gift, passion or skill.

For Alabama State University alumna Barbara Williams, this is exactly what fueled her journey that not only influenced her life but the generations after. With decades of dedication and work attached to the university’s athletics department, it is because of her that the women’s sports program was started in 1975 with basketball and eventually expanded to track and volleyball soon after. The impact of laying the foundation for all women’s sports and expanding to its current prestige and notoriety cannot be understated. Her legacy has affected thousands, all while putting her alma mater’s name on the map.

A native of St. Petersburg, Florida, Williams is the third of 10 children, five sisters and four brothers. Williams grew up in Valley, Alabama, with her grandmother, where everyone in the neighborhood helped to rear a child. Growing up, her family had everything they needed and sometimes the things they wanted when her grandparents, Effie and Lewis Keller, could afford it. Overall, she was happy with what they had.

There is a saying, “it takes a village to raise a child,” and Williams learned so much from her grandmother. She describes her as a woman of great faith who believed that respect for your neighbors was a commandment. She also taught her about having a green thumb in gardening and flowers. The family had a garden every year and supplied the whole neighborhood with fresh vegetables.

Everyone in the house was required to attend church. The Bible was important in their rearing because living a Christian life was her way of making sure they had a well-rounded life.

Not working was not an option. It was expected of Williams and all her sisters and brothers.

“I was happy going to work with her (grandmother) earning money cleaning areas that she could not,” Williams said. She describes one bright moment working with her during the summer after high school graduation. Going to college meant everything to her and her grandmother. Earning enough money for college was always on their minds. Although her grandmother did not have the money for the Valley, Alabama native to go to college, she always believed God would work it out. During that summer, Williams earned $138 to help with her finances to attend college, which began two weeks later.

It did not take long for Alabama State University to be placed on Williams’ radar as a child. In high school, she was a majorette, and it was in that position where Williams got her first taste of the annual Turkey Day Classic activities. From the parade to the bands and performances, there was something about the Turkey Day air that Williams claimed, “It felt so good.” This young love and attachment ultimately incited her decision to attend Alabama State University.

When Williams arrived on campus to start her collegiate journey, she was met with pushback, as many HBCU students can relate to, financial aid. Having nine other siblings under the care of her grandmother, Williams made it her mission to attend college. However, when she arrived, the Office of Financial Aid was not able to help her with her expenses.

Williams went through the chain of command to the director of Financial Aid, who was out of his office and away on vacation at the time. The next person she talked to was the president of the university, Levi Watkins Sr., L.H.D. Upon hearing her situation and pleading that she “had to go to college,” Watkins made the necessary calls to ensure she was taken care of. Along with this, Watkins made the humanitarian effort to take Williams into his home and care for her in the president’s House on campus. In her early days of staying with Watkins, Williams would cook breakfast with Watkins’ wife, Lillian Watkins. It was there where she learned to make his eggs and bacon the way he liked it — scrambled soft with the bacon consistency between crispy and tender. Since that experience, Williams has prepared her breakfast the same exact way.

Williams described her time living at the University President’s house in her freshman year as being an extended member of the Watkins family. Wherever they went, she followed, rather that being football games, Magic City Classic, or Homecoming. During her sophomore year, she departed from the president’s home and began staying in the residence hall on campus, immersing herself in the full college experience. During this time, the caring and bubbly personality of Williams would begin to sprout.

She recounts a memory where she walked out of H. Councill Trenholm Hall and encountered a woman by the name of Mrs. Fleet, who happened to be wearing “a gorgeous sweater.” Williams inquired where she could purchase the sweater, even asking if it was available at the bookstore. Unbeknownst to her, the sweater was a sorority sweater for the members of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. Upon learning this, Williams vowed to Fleet that she would become a member. In 1975, Williams became a member of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. and later served as the chapter adviser.

During her time at O’Mother Dear, Williams depicted the experience and tone on campus as more exciting to be a part of the student body with athletics.

“Nothing other than high school games were on campus … nothing to do on campus for girls.” Women did not have much and were mostly limited to intramural softball. Because of this, Williams spent a good majority of her time participating in the choir and theatre.

Williams graduated from Alabama State on June 6, 1972. She would attend graduate school during the summers of 1974-76 at Indiana University. It was at Indiana University where she met and worked with Sam Bell, the university’s track coach. The interaction with Bell helped her get appointed as the university’s coordinator of women’s athletics. Under this role, she was now able to work directly to bring change to the sports programs and athletic director Ulysses McPherson.

Williams had the task to generate interest for women’s sports, a project spearheaded by McPherson. The Title IX law was put on the books in 1972. It became very important and critical to women and the engagement to provide and open up the mentality for women to participate in sports. An action that was highly considered taboo.

The first thing Williams was advised to do was establish a vision, something to attract the people to be a part of the bigger picture. Williams’ vision was to hunker down on the main job, ensuring they get an education and graduate. Instilling in them that “they can be somebody” and to remain themselves.

“Be true to yourself,” Williams said. “Be honest with yourself and be honest with others. Do not let some failures be your end, but your beginning to make sure you can be what you were trying to become.”

This mindset, along with the work ethic, helped to push McPherson and Williams’ vision of the women’s athletic department where it needed to be. Soon after, in 1975, women’s basketball made its debut, followed by track and field and volleyball. Williams would then coach the basketball and track team that same year. When asked to describe the mindset and perspective she was in in the midst of the moment, it brought to mind a mantra she and her son frequently say, “No matter the trials and tribulations, I refuse to be outdone.”

Williams was the only woman to bring three sports together in the same year. “It was fulfilling a desire and from what I noticed the university lacked,” she said. William’s hard work and dedication to the insurgence of women’s athletics is the reason why she resembles a pioneer and trailblazer.

Williams is quick to emphasize that she did not act alone. Her leading the program also caused the program to need help from people higher up the power chain. Three people who contributed heavily with responsibilities and helped the program develop were John Gast, Samuel Smith, and Horrace Townsend. They made and molded the process to become a strong basketball program.

As a coach, Williams had an impressive career in both sports. In her basketball tenure, she finished with a 95-23 record and a SWAC Championship in 1989. However, it was not just the play on the court where Williams’ impact was felt. Former student-athlete Michelle Simmons became the head coach at Carver Senior High School in Montgomery, Alabama and captured an extraordinary 287-61 record. Simmons would win nine straight area championships, the 1995-95 regional championship, the ‘93 state championship and ‘88-89 state runners-up.

Williams would then focus her talents on the track team, coaching them for 25 years, earning multiple first-places and top-two finishes. One of her biggest accomplishments would be having an athlete compete at the highest level of athletics. Lillian Cole competed in the 1984 Olympic Trials, giving nationwide attention to the school. The Alabama State University Women’s 4×100 Relay team would also be featured in the Track & Field News Magazine.

When asked how it feels seeing the evolution of women’s sports and the prestige the recent teams have garnered, Williams said she “feels ecstatic… like a proud parent.” She loves how the young ladies’ lives are being appreciated. Today, Williams finds herself attending many women sporting events around the campus and coaching in the stands.

The progress and dominance many women teams have accomplished recently, such as the softball, soccer, basketball, and track teams, would not be possible without the foundation that Williams put into place. However, she does mention that she has some sad spots that she wishes would change and evolve.

She notes that student participation is not really there. For double-header basketball games, most students do not arrive until the halftime of the girl’s game. “And even when they show where is the school spirit? Why can’t ASU, the whole student body, not just Street Team, have a sense of support and patronage? Everyone out, everyone wearing gold. From the students, staff and even the local community.” She feels the sense of school spirit and Hornet pride lacks compared to other universities such as Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University or Jackson State University.

Years ago, the essence of the university and activities that were held were fun and enjoyable. Williams notes that she has seen the change come across the school from year to year since she was a student to a coach to a professor. There has been a deterioration of the culture of the school that she believes could be due to the rules and regulations and not enough outlets.

She recalls memories of students having to bus to the Crampton Bowl to attend the football games and the sense of connection that the university had with its students. Now with a multi-thousand stadium, there is a disconnect for this generation. Williams believes former and future presidents need to bring in different avenues to get students involved on campus. If not, students are not going to engage.

According to Williams, “The administration has a Laissez-faire attitude of ‘if it goes it goes, if it does not, it’s whatever,’ but drive needs to come from every entity of the administration, the administration needs to be a shaker.”

Williams would go on to say, “ We seem so conservative on campus … students should have more freedom to be out. Be a student.” She remembers cook-outs and barbecues that would take place around the campus — eating lunch in the quad or amphitheater. In the past, there were several gatherings together and there was not a sense of being separated. Parades on campus and even competitions between different dormitories. Even the times when teachers would dismiss class early or cancel class because they knew of the yearly homecoming activities. It is actions like this that create an element of pride and worthiness to not only the student but to the university as well to enjoy this time and add flavor to our lives as college students, according to Williams.

“ASU should feel like home,” Williams said.

She feels strongly about involvement being key for the students, even things as simple as a sack race or staff versus student basketball game. “Creativity must generate interest for students.” Her immense pride and personality of dedication for the school remain strong even after all these years because she feels, “I am still a student at heart.” She understands that the mental, social, and environmental aspects play a role in optimal health and Hornet pride and what you put in those to say, “This is my O’ Mother Dear.”

The Williams legacy continues as two of her children graduated from Alabama State University. Robert A. Williams, Jr. graduated from the University in 1999 with a bachelor of science degree in science. He is currently a Science teacher at Banneker High School in Atlanta, Georgia. Williams Jr. is STEM certified and has taught science in Dubai for three years. Bridgette A. Williams is currently employed with Montgomery Public Schools and has been with MPS for 25 years. She has a bachelor of science in English/language Arts ‘96, a master of education in English education ‘99, a master of arts in school counseling in 2010, and an education specialist degree in school counseling in 2014. Gegiyah Southall is currently employed with Montgomery Public Schools and graduated from the university in 2009 with a bachelor of arts in theater arts.

The legacy continues to another generation as two grandchildren also have ties to the school. Mercy Shinteale Williams, a transfer student from Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical University, is currently a senior attending Alabama State University with intentions of receiving a bachelor of arts degree in psychology during Spring 2022, and Brielle Cheanese Harris graduated from the university in spring 2021 with a bachelor of science degree in criminal justice. She plans to pursue a graduate degree in cybersecurity.

Williams stands strong on being able to be a light that provides a direction for students.

“Giving them the encouragement to feel like they are somebody,” Williams said. “I believe that in time changes will take place because everything must change. I also believe that one person can make a difference because if you have an idea, someone else will pick it up and help it to grow. This is what has happened and will continue to happen.”

Joyce Wright Moss, Ed.D. • Jan 11, 2022 at 6:53 pm

Congratulations to my Freshman friend; Proud of you.

Joyce (Wright) Moss and Dwight

Elsie Hales • Jan 11, 2022 at 2:24 pm

What a great and uplifting story to read and so proud of your accomplishments.